The Instagram Life: A Selection from David Brooks’ The Second Mountain (2020)

“Some people graduate from college with the mindset of daring adventurers. This is the time for fun before real life settles in. Marriage and a real job will just arrive in the mail one day when they are thirty-five. In the meantime, they’re going to have experiences.

These are the people who at age twenty-three go teach English in Mongolia or lead white-water rafting trips in Colorado. This daring course has real advantages. Your first job out of college is probably going to suck anyway, so, as the impact investor Blair Miller advises, you might as well use this period to widen your horizon of risk. If you do something completely crazy you will know forever after that you can handle a certain amount of craziness, and your approach to life for all the decades hence will be more courageous. Furthermore, you will build what the clinical psychologist Meg Jay calls ‘identity capital.’ At every job interview and dinner party for the next three decades, somebody will want to ask you what it was like teaching English in Mongolia, and that will distinguish you from everybody else.

This is an excellent way to begin your twenties. The problem with this kind of life only becomes evident a few years down the road if you haven’t settled down into one thing. If you say yes to everything year after year, you end up leading what Kierkegaard lamented as an aesthetic style of life. The person leading the aesthetic life is leading his life as if it were a piece of art, judging it by aesthetic criteria—is it interesting or dull, pretty or ugly, pleasurable or painful?

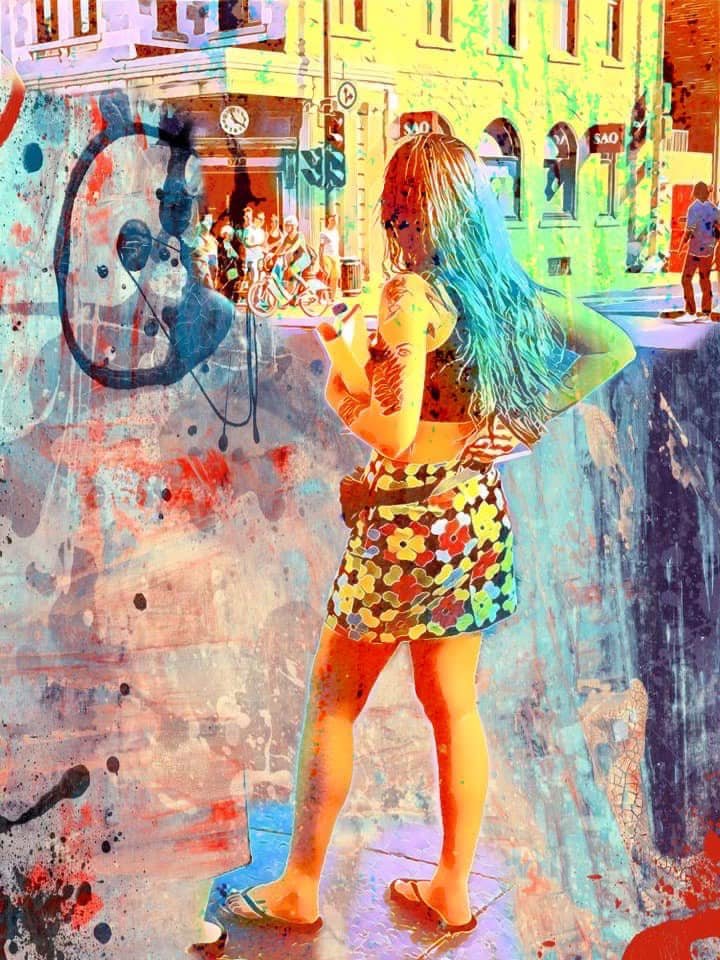

Such a person schedules a meditation retreat here, a Burning Man visit there, one fellowship one year and another one the next. There’s swing dancing one day, SoulCycle twice a week, Krav Maga for a few months, Bikram Yoga for a few months more, and occasionally a cool art gallery on a Sunday afternoon. Your Instagram feed will be amazing, and everybody will think you’re the coolest person ever. You tell yourself that relationships really matter to you—scheduling drinks, having lunch—but after you’ve had twenty social encounters in a week you forget what all those encounters are supposed to build to. You have thousands of conversations and remember none.

The problem is that the person in the aesthetic phase sees life as possibilities to be experienced and not projects to be fulfilled or ideals to be lived out. He will hover above everything but never land. In the aesthetic way of life, each individual day is fun, but it doesn’t seem to add up to anything.

The theory behind this life is that you should rack up experiences. But if you live life as a series of serial adventures, you will wander about in the indeterminacy of your own passing feelings and your own changeable heart. Life will be a series of temporary moments, not an accumulating flow of accomplishment. You will lay waste to your powers, scattering them in all directions. You will be plagued by a fear of missing out. Your possibilities are endless, but your decision-making landscape is hopelessly flat.

As Annie Dillard put it, how you spend your days is how you spend your life. If you spend your days merely consuming random experiences, you will begin to feel like a scattered consumer. If you want to sample something from every aisle in the grocery store of life, you turn yourself into a chooser, the sort of self-obsessed person who is always thinking about himself and his choices and is eventually paralyzed by self-consciousness.

Our natural enthusiasm trains us to be people pleasers, to say yes to other people. But if you aren’t saying a permanent no to anything, giving anything up, then you probably aren’t diving into anything fully. A life of commitment means saying a thousand noes for the sake of a few precious yeses.

When enough people are going through this phase at once, you end up with a society in which everything is in flux. You end up with what the Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman calls ‘liquid modernity.’ In the age of the smartphone, the friction costs involved in making or breaking any transaction or relationship approach zero. The Internet is commanding you to click on and sample one thing after another. Living online often means living in a state of diversion. When you’re living in diversion you’re not actually deeply interested in things; you’re just bored at a more frenetic pace. Online life is saturated with decommitment devices. If you can’t focus your attention for thirty seconds, how on earth are you going to commit for life?

Such is life in the dizziness of freedom. Nobody quite knows where they stand with one another. Everybody is pretty sure that other people are doing life better. Comparison is the robber of joy.

The person who graduates from school and pursues an aesthetic pattern of life often ends up in the ditch. It’s only then that they realize the truth that somehow nobody told them: Freedom sucks.

Political freedom is great. But personal, social, and emotional freedom—when it becomes an ultimate end—absolutely sucks. It leads to a random, busy life with no discernible direction, no firm foundation, and in which, as Marx put it, all that’s solid melts to air. It turns out that freedom isn’t an ocean you want to spend your life in. Freedom is a river you want to get across so you can plant yourself on the other side—and fully commit to something.”—David Brooks, The Second Mountain: The Quest for the Moral Life (2020)